Blazing The Motor Trail To Auckland

BY ARTHUR CHORLTON

When the main trunk railway was opened, towards the end of 1908, the motor-car was already in New Zealand, but it had not, in the special sense, yet arrived. That time did not come till nearly twenty years later with a general improvement of roads.

Having done the journey between Wellington and Auckland, first by rail and steamer, and then by the Main Trunk, I became interested in the possibility of a motor trip between the two cities through the King Country.

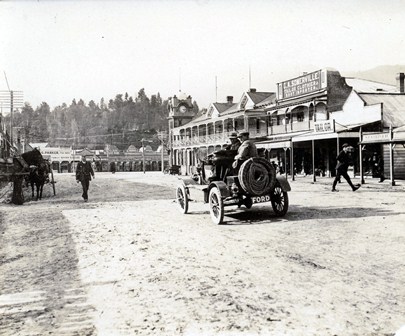

There was only one car for a job like that the old Ford Model T. It was not old then-1912-and was by no means "The Universal Car" Henry Ford claimed it to be, at least not in New Zealand. The Colonial Motor Company fell in with my proposal, provided the car, a three-seater, with full equipment and sponsored the expedition.

The party of three comprised Harold Richards, a first-class driver, the late Ernest Gilling, press photographer, and myself as manager and guide.

Taihape was reached at 4.15pm that day.

Taihape was reached at 4.15pm that day.

The start was made on Friday, November 22, 1912 from opposite the old entrance to the GPO. Taihape was reached at 4.15pm that day, after an unventful run of 1412 miles at an average speed of 22 miles an hour, which was not bad with the old Paekakariki Hill and roads as they were then.

From now on to Te Kuiti we were in totally un-motored country, except for a doctor's single-cylinder De Dion in Taumarunui, landed by train and marooned there ever since. People, horses, cattle and dogs were scared at the sight of the horseless carriage, and outside Raetihi, a woman wheeling a pram upset it with the baby in a panic stampede.

After a night encamped under a fly by one of the Main Trunk viaducts near Pokako, the motor pioneers, jubilant at their progress, went on over the plateau at Waimarino and down past the Spiral to Raurimu. All was going well and it was a lovely Sunday, with prospects of being in Taumarunui in the early afternoon.

But the unexpected happened. At Oio one of the service bridges over a creek built for railway construction out of timber from the bush had rotted away and collapsed. This looked like the end of the adventure. It was only a little stream in a deep gully, but Model T's are not tanks, and there seemed little chance of getting across.

Fortunately there was some new timber for a new bridge, handy on the spot, and the pioneers, reinforced by timber-workers from a nearby bush sawmill, off work for the Sabbath, in a few hours erected a sort of Bailey bridge and Taumarunui actually was reached after all that evening.

But beyond Taumarunui there was a blank, and when the motor pioneers set out again for the north on Monday, the fourth day out from Wellington, it was a genuine adventure into the unknown.

There was no road up the Ongarue Valley, only a grass-grown track on the wrong side of the river which sooner or later would have to be crossed to get to Ohura and the Waitewhena. To cap it all, it had begun to rain and the day looked ominous for a deluge. But there was no going back and the pioneers pushed on.

It was here they struck their greatest piece of good luck of the whole trip. At Okahukura (Te Koura as it was called then) they found Public Works men on the Stratford Main Trunk railway construction had built a service road over the hill to Matiere and a bridge over the Ongarue!

The road was rough and the climb high, but the Ford, in heavy rain, made nothing of it, and the party was in Matiere for lunch. In the boarding-house a local celebrity led the party into taking a supposed "short cut" to Aria, quite off the intended route via Ohura and Waitewhena.

Broken bridge at Oio

Broken bridge at Oio

Less than a mile from Matiere and in full sight of the township the motor travelers were so hopelessly bogged that they could make no headway with block and tackle and had to call on a nearby farmer for horses. It took four of them to pull the Model T out of the quagmire and over the hill.

The next two days were sheer misery. Without horse traction, in the papa mud and rain, corduroying patches and using a greasy block and tackle, the pioneers could only make four miles the first day. Even tanks would have been hogged under such conditions. It was a job for "ducks," if there had been any then; if not, for horses.

So horses it was when at last they could be procured, and for all the next day the pathfinders worked in convoy with an escort of two stout draught horses and their owner, running the car, under its own steam, whenever possible, and waiting for the horses when halted by a morass of mud.

The seventh day involved much road making and cross-country running in the upper Waitewhena, hitherto untouched by wheeled vehicles of any kind. The settlers went on horseback or used sledges and packed their cream to the factory.

But the weather was fine at last, and after some close shaves in the wilderness, over punga bridges, and on narrow tracks, crowded by slips to the edge of precipices the pioneers emerged from the bush at Aria, and reached Hamilton at the end of the eighth day.

Thence to Auckland took only half a day, and the battered, mud-stained Model T, with its weary, unkempt voyagers, ran down Queen Street, crowded with staring people just off work, and pulled up at the G.P.O. at 1.20 p.m., Saturday, November 30, 8 days 13 hours from Wellington.

It is some commentary on the time taken to add that the same car, stripped of all impedimenta, made a racing run home to Wellington, via Taupo, Napier, and the Wairarapa, in 2½ days (22 hours’ running time). It was years before this record was beaten or the pioneering journey through the King Country was repeated.

|

|

|

| Twixt cliff and chasm | Auckland at last after eight and a half days. | Home in Wellington again |

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Arthur Frederick Thomas Chorlton is one of those interesting people who have done many unusual things. Apart from his Oxford classics training, he was an early Wellington cricketer and wrote poetry. One-time farmer, teacher, motoring veteran, and for nearly 40 years a journalist, Chorlton wrote the first motoring “column” in New Zealand – for the Wellington daily Evening Post back about 1910 under the nom-de-plume of “Athos”. Athos is Greek for I, myself, but was also, appropriately, happily close to the word autos.

Chorlton covered some of the earliest motor trials in New Zealand - held in Reuben Avenue, Brooklyn; then one of the steepest streets in Wellington. No trouble to modern vehicles, it was a stiff test for the cars, trucks and motor-cycles of those days. Prior to settling in New Zealand Chorlton saw the coming of the motor car age in England in the 1890s, a brother actually owning one of the first models – a steam job.

Chorlton nearly created what might have been the prototype of our modern “duck” military vehicle. He had designed a fully amphibious Model T Ford equipped with folding pontoons and a friction drive to propellers for river crossings. World War I intervened in those plans. Even so, while he was with the Services, Chorlton was still associated with motoring and drove a Model T in the Sinai Desert, and the invasion of Palestine. Besides the pioneer trip described here,

Chorlton made many other notable trips by Model T. One was to the steamer Indrabarah, which ran aground in the Rangetikei River mouth. Chorlton travelled by Model T from Bulls, through the loose sand-dunes from Flock House to the beach to cover the story for the Evening Post. The Indrabarah, apparently hopelessly stuck fast, confounded everybody by blithely sailing into Wellington a few days later.

Incidentally, Chorlton’s story, Blazing the Motor Trail to Auckland, featured in the English Motor magazine, creating considerable interest. Chorlton also published Motor Pioneers through The King Country, an 80 page foolscap book, complete with some 130 of Gilling’s often dramatic photographs taken on the journey in 1912; and this book has just been re-published and is on sale from this website (click the ‘FOR SALE’ key on the HOME page).